Claudine’s House

Inspired by the 1922 eponymous novel by Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, Claudine’s House features work by Katherine Auchterlonie, Anders Hamilton, Peter Hoffmeister, Athena LaTocha, Masha Morgunova, Taylor Marie Prendergast, and Dominik Tarabanski.

On view at Ross + Kramer Gallery New York, July 10–September 13, 2025.

Curatorial Statement

“With Claudine’s House, I’ve set out to capture the emotional timbre of Colette’s writing—the quiet ache of remembering, the vibrancy of youth, the sacredness of place. I find in Colette’s writing qualities that are often unique to visual art. She rarely assigns overt emotion, instead relying on precise, sensorial description to evoke feeling. Colette observes the world with a delicate, meditative detachment. Her prose lingers on the details of everyday life—furniture bathed in afternoon sun, the scent of damp earth, the rhythm of rural routines, the affairs of the cats, dogs, insects and other animals that were as much kin to her as her own mother and father—and through this careful rendering, emotion emerges naturally. The reader experiences whispers of their own memories, nostalgia, the preciousness of life, the sting of longing, not because Colette tells them to, but because the scenes she paints are so vividly alive that they resonate unescorted by a prescription of emotion. This restraint gives her work a contemplative, almost impressionistic quality, inviting us to feel more deeply, more precisely, because she never forces us to. Writing and visual art may not always be such natural friends but the two disciplines converge here—existing as a free-flowing translation of experience, an act of unadulterated remembrance. We can often find the most sincere meaning and beauty in works of art that express with tender abandon, works that do not, by virtue, designate their own fixed message. In this way, we engage with the artwork not just as observers but as collaborators in meaning-making, shaping the work as it shapes us.”

Katherine Auchterlonie

In her paintings, Auchterlonie employs a fluid, organic system of abstract notation—one she has developed through an intuitive synthesis of “plein air” impressionistic sketches and diverse scientific references, including medical illustrations, dance notations, mathematical symbols and ancient pictographs. This visual language is not fixed; it moves and morphs with the artist's marks shifting, blending, colliding, hanging from one another to form larger dynamic structures that often mimic flora, fauna, and elemental forces. Out of these gestures, a kind of landscape emerges, an emotional topography that reaches beyond the purely visual into the realm of felt experience.

Like Colette, Auchterlonie approaches expression through observation, recounting deeply emotional and complex experiences through their textures, scents, movements, and atmosphere. Both artist and author offer their scenes not as fixed narratives, but as open invitations. They create an environment that the viewer or reader is encouraged to explore, interpret, and connect with through a deeper exploration of their own experiences. As such, the work becomes not just a representation of experience, but a catalyst for it—transforming subjective moments into something shared, evolving, and infinitely interpretable.

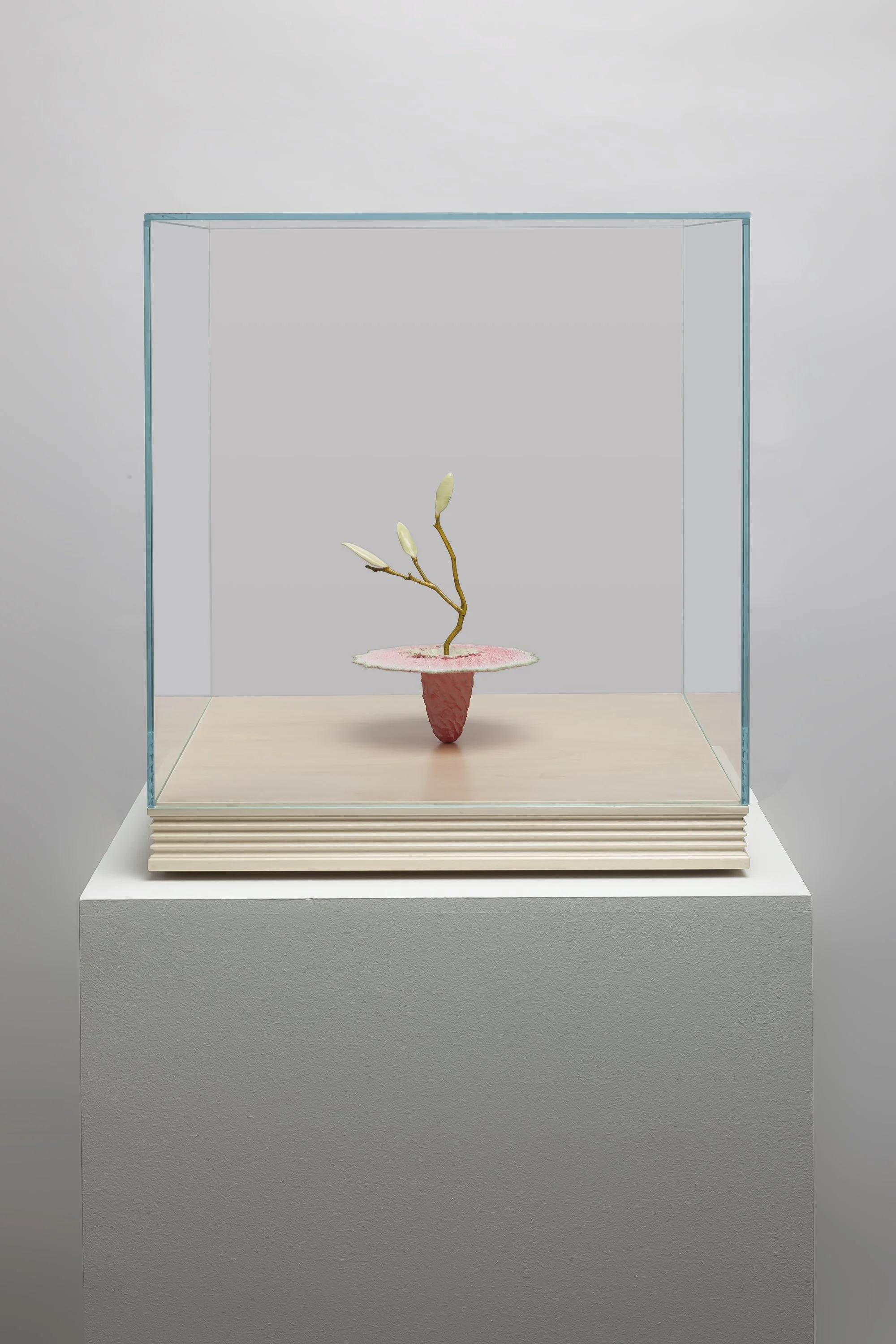

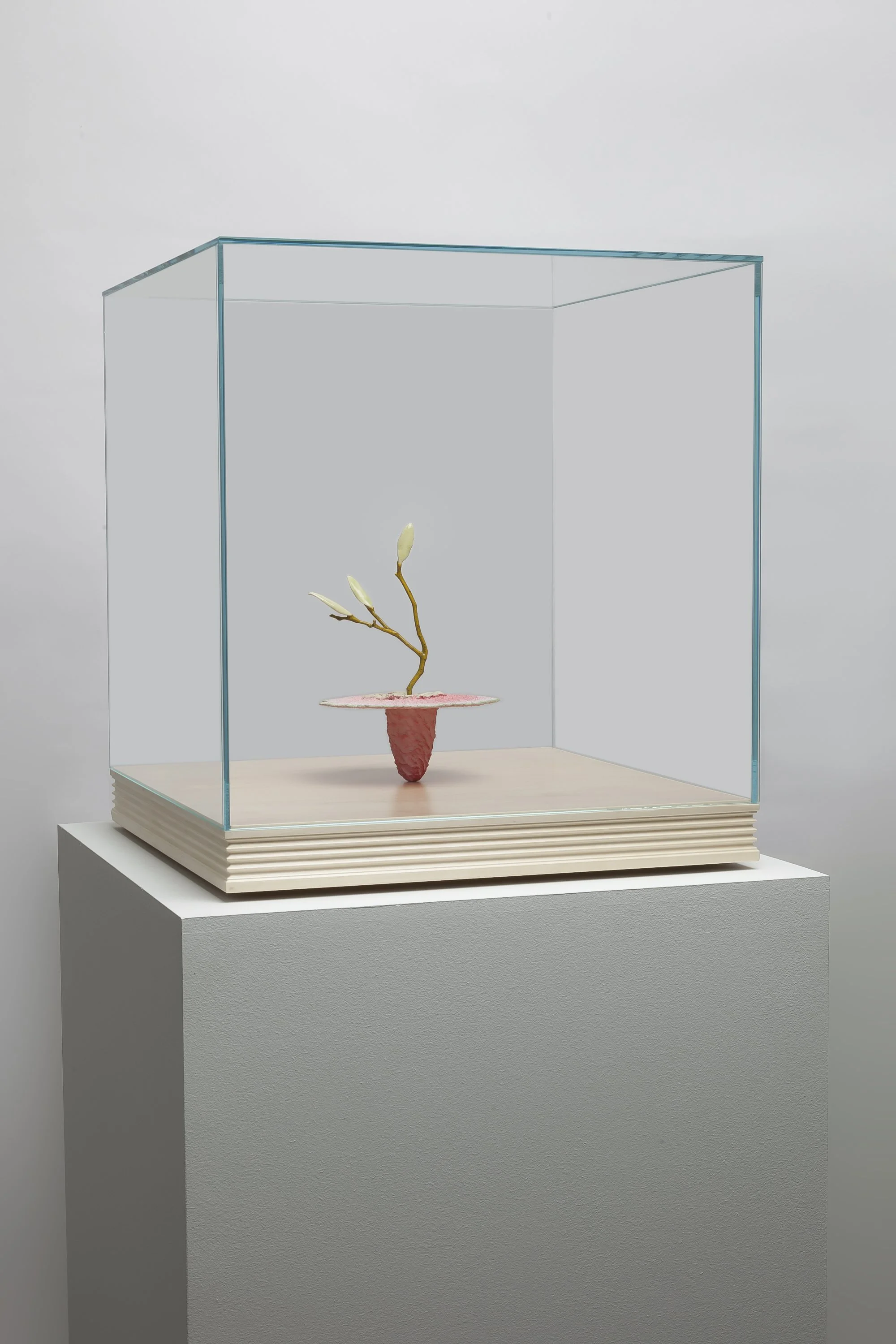

Anders Hamilton

A distinct sense of preciousness permeates Colette’s writing—each moment is encapsulated, each tiny thing is beautiful, no one more important than the other. Anders Hamilton’s sculptures evoke a similar reverence. The artist collects leaves, flowers, and twigs from the areas surrounding his home and studio. They are then brought into the studio, where the twigs are dried and coated in resin to preserve their fragile architecture. Leaves and petals are dipped in slip, then subjected to the heat of the kiln, where they are incinerated—what remains is their ash, sealed within a ceramic shell that retains the memory of their original form. The leaves and petals are then coated with glazes containing rare earth elements. Once fired, these glazes exhibit unique dichroic properties—subtly shifting color in response to natural or artificial light. A single surface might present a light sage green in daylight, then shift from grey to violet under artificial light.

Both Hamilton and Colette offer contemplative meditations on transformation—particularly the passage from life to death, presence to memory. While Hamilton’s sculptures may appear inert or enshired, like relics or fossils, they retain an aliveness through their responsiveness to light. Colette’s memories, too, are held gently but never frozen, they are dynamic in their emotional resonance. Together their works invite us to consider that what may be gone from us is at once still alive. The past continues to speak—shifting shape, revealing new meanings, and teaching us anew as we carry it forward. In their hands, absence becomes a space of ongoing revelation.

Peter Hoffmeister

Peter Hoffmeister and Colette both navigate forces of permanence and erasure, exploring how memory is shaped, preserved, and ultimately surrendered to time. Hoffmeister’s gravestones acknowledge their own impermanence with surfaces that are worn, cracked, and layered with glazes and oxide washes that suggest moss, lichen, and age. Their surfaces embody memory—imperfect, softened by time, subject to distortion and eventual disappearance—and become an epitaph in their own right. Just as slate gravestones flake apart, their inscriptions lost to weather and growth, so too do these ceramic works embrace the slow fading of the individual, replaced by texture, tone, and the ghost of form. Hoffmeister’s most recent body of work draws a parallel, on many levels, to the following passage from Claudine’s House:

“...I followed my brother to the loft. On a trestle table he cut out and stuck together sheets of white cardboard, which he shaped into flat slabs, steles rounded at the top, or rectangular mausoleums surmounted by a cross. Then, in ornate capital letters, he painted epitaphs on them in China ink: long or short epitaphs that perpetuated, in pure ‘marbler’ style, the sorrows of the living and the virtues of some imaginary departed person.”

“...A day came when the rough floor of the loft was no longer good enough. My brother decided that he wanted to honour his white tombs with soft, fragrant earth, real grass, ivy and cypress trees... At the bottom of the garden, behind the grove of thuja trees, he found a place for his dear departed with their resounding names: there were so many of them that they overflowed the lawn, strewn with marigold heads and little wreaths of beads. The diligent gravedigger would scrutinise them with his artist’s eye.

‘That looks really good!’

After a week, my mother happened to pass by that way, and stopped, flabbergasted, staring with all her eyes—pince-nex, lorgnette, and glasses for distance—and uttered a cry of horror, violating all those burial places with a kick of her foot...”

“...She gazed at the culprit across the abyss that separates a grown-up from a child. With angry pulls on her rake she swept up the gravestones, the wreaths and the broken columns. My brother endured without protest this public obloquy meted out to his labours and, staring at the denuded lawn and the hedge of thujas which cast its shade onto the freshly raked soil, he called me to witness, with a poet’s melancholy:

‘Don’t you think a garden without tombs looks sad?’

For the exhibition, Hoffmeister selected 16 gravestones and wrote an accompanying poem, each line of the poem serving as a title of a gravestone:

here lies

one____here lies

two____the grass, as

three____we lie

four____in memory,

five____a shovel

six____full of (earth),

seven____a memory born

eight____whole,

nine____dug deep

ten____to the core,

eleven____which becomes

twelve____more soil,

thirteen____more earth,

fourteen____to

fifteen____be

Sixteen____dug

Athena LaTocha

Athena LaTocha’s work is deeply rooted in place. The artist’s process begins with immersive visits to specific sites, where she engages not only with the visual landscape but also with its textures, fragrances, histories, and spirit. From these environments, LaTocha gathers materials including rocks, sediment, minerals, and wood. The Night Has Come, The Land Is Dark (2025) incorporates elements collected during her residency at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, including mica from the historic Palermo Mine No. 1, sediment from a nearby gravel-washing pond, and wood that LaTocha charred herself to produce charcoal. These materials carry the memory of extraction, of fire, of decay, and rebirth. In LaTocha’s work, the land is not simply depicted, it becomes the medium through which its own story is told.

In LaTocha’s work, the viewer is enveloped by an image that is environmental in both its subject matter and scale, one that obscures the boundary between abstract artwork and natural event. LaTocha often floods her surfaces with large volumes of ink wash, water, or solvents and scatters sediment, minerals, and pigments by throwing them across the paper, dropping them from above, or pounding them into her compositions with rocks, bricks, metal and other tools. Nature itself is rendered as painter and sculptor, while LaTocha channels these forces with a sense of ritual and forcefulness. In The Night Has Come, The Land Is Dark (2025), dark ink films sweep diagonally across the surface like a landslide, with scattered mica gleaming like ancient stars. There’s both beauty and ferocity here, the textured surface evoking the impact of time and touch—human or elemental. LaTocha’s methodology mirrors the very natural forces she is referencing: sculpting by sedimentation, coloring by fire, shaping by pressure. She replaces the brush with debris, her unconventional tools—tire shreds, bricks, rocks, and scrap metal that she has collected—reveal an ardent curiosity, a trust in the chaotic and the uncontrollable.

With Claudine’s House, Colette’s depiction of domestic life—its dramas shaped by the cycles of seasons, animal behavior, and the passage of time—brings the reader to consider how deeply nature and our environment impacts who we are and who we become. Similarly, LaTocha’s work offers nature not only as subject but as co-creator. The artist’s work is an act of listening—listening to land and its history. It is also an act of offering, capturing the moment where volatility becomes form, where history becomes surface, and where place finds the ability to speak for itself.

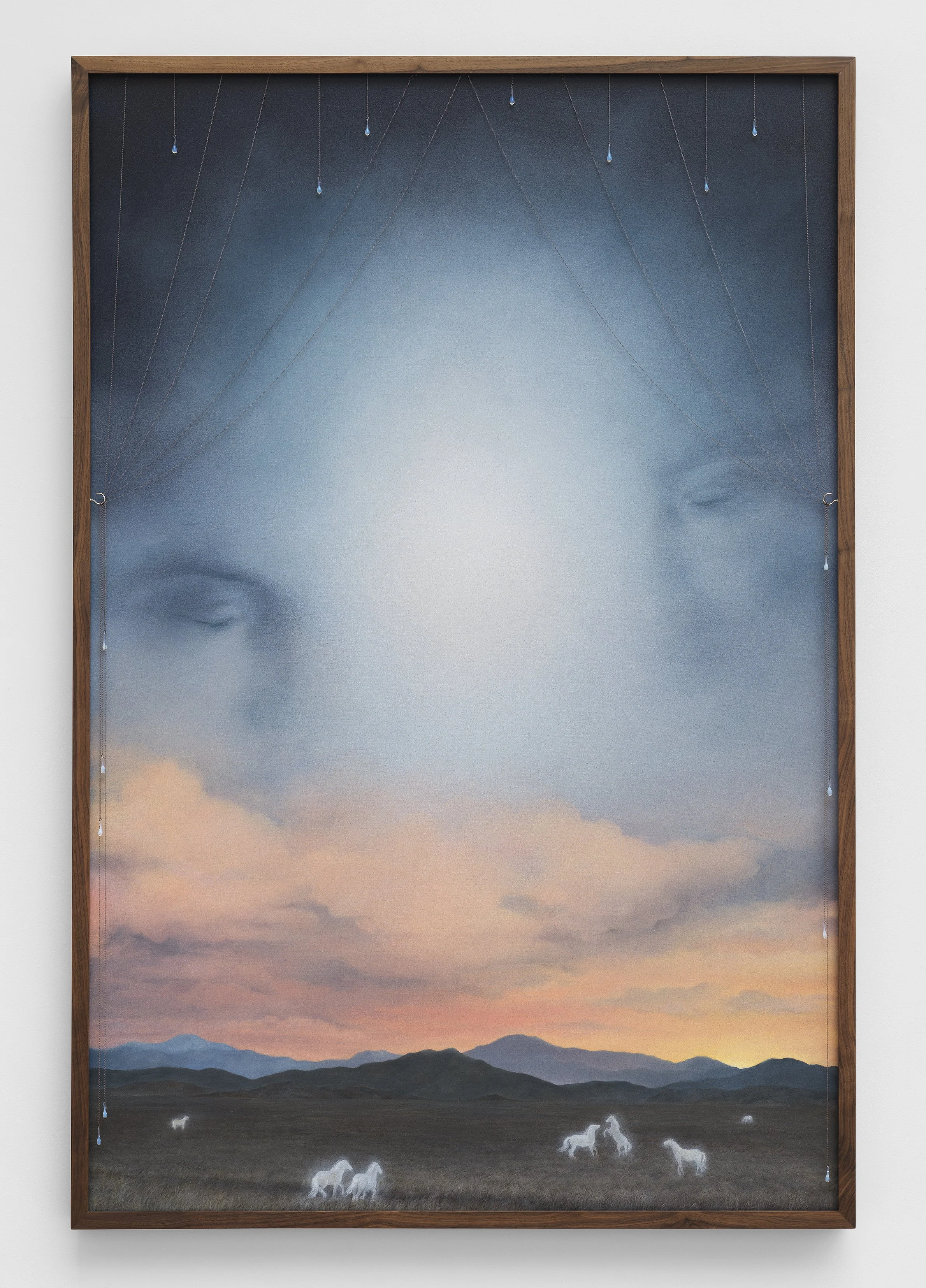

Masha Morgunova

Masha Morgunova’s works meditate on memory and impermanence. In House of Light (2025), suspended glass droplets populate the space of a half-collapsed ceramic house—tiny orbs of remembrance that embody both lived experiences and the emotional remnants they leave behind. In their translucency and fragility, these glass forms evoke the ephemeral nature of memory, and the way space—especially home—acts as a vessel for both joy and sorrow. Morgunova’s work invites viewers to consider how spaces retain the imprint of human presence by holding silence, grief, laughter, and transformation. This sensibility echoes the themes of Colette’s Claudine’s House, in which the domestic space becomes a central repository of personal and collective memory. In both Colette’s writing and Morgunova’s work, the house is not static—it is animated by past lives, by feelings that resist time.

Morgunova offers two prose poems that exist in conjunction with her visual work included in the exhibition:

House of Light

On this grey day I am somewhere far and foreign, confronted with a somber sight: a lifeless outline of what used to be someone’s home. With its walls succumbing to the unrelenting work of the elements, the house is half-collapsed and almost entirely see-through. It feels wrong to have inward displayed outward, but the resilience of its remaining parts evokes deep respect; while I am hesitant to enter, I eventually choose to proceed.

When inside, the absence of a complete home is so striking that I instinctively seek to return to the one that’s immortal, buried deep within my heart. I close my eyes and notice the place change, becoming simultaneously alive with what once was and what could have been. Cool air turns into the inviting warmth of a fireplace, the smell of dampness into that of freshly baked rye bread. Within the sound of grass brushing against the crooked walls I hear a child’s whisper. Whether these remembrances are others’ or my own, they start flooding the space and in doing so pierce my heart with a million fine needles of great sorrows and even greater joys. I have never felt so full, and so invisible.

It is hard to breathe, so I stop. My heart slows down. With fewer distractions, I feel unusually quiet and reopen my eyes. In this newly found silence it is easier to see the house for what it really is: a perfectly complete home for the tree that rests in the middle of it, for the rainwater that cries all over its walls, for the ripe berries that grow freely in the absence of a floor. What agreeable, good-natured residents. In the rustling of wind I hear a quiet sigh of relief.

And so absence reveals presence, and I catch myself smiling with ease. As the clouds move over to reveal the sun, I choose to stay a little longer, wondering silently at this sight of ruins, absorbed by the brilliance of light that falls on them with grace.

Dreamweavers at Work

Exhausted after a day of work and play, the child stretches out on a soft bed of dry grass, her eyes finally resting on the sky. With a head full of stories and the heart of a dreamer, she knows that anything is possible under her lazy gaze; feeling mildly mischievous, she lets go of the reins.

The clouds see the child and yield to her polite request for whimsy. Moving slowly and silently, they begin to shape-shift into familiar silhouettes; and so a ring turns into a butterfly net turns into a sword. Many objects pass through the sky before the girl’s yearning for the animate is noticed. Gathering all their might, the clouds morph into a blurry vision of her most desired visitor, her mother: the way she best remembers her, looking like she could be her older sister's older sister. The child feels the grass become warm, like the touch of familiar hands. The wind blows gently to pass along an embrace. Time is slow and irrelevant; she closes her tired eyes to savor the moment.

When the child notices approaching sleep, she welcomes it without hesitation. With eyelids closed, she is once again looking at the sky, only now it is the color of a ripe summer peach. She turns her head to face the fading light and sees a small herd of horses, so white they look like luminescent ghosts in a land of growing dusk. One of them comes closer with what seems like a greeting, slightly bowing its big and beautiful head. Larger than any animal the child has ever seen, it has a glowing mane and long, curly eyelashes. The rest follow suit, and shortly after all are united in what looks like a euphoric dance, breathing in full lungs of crisp air, feeling incredibly alive after breaking the spell of their respective solitudes. The child marvels at the animals’ agility and unbounded freedom, and the animals marvel at her playfulness and capacity for wonder. The last rays of sunshine illuminate their shared joy, while eternity, felt but unseen, fuses with the present.

When the child awakens, her cheeks are wet from feeling something she knows to be important, although it will take years before the right language finds her. For now, she is blazing with excitement to tell her sister of the giant glowing horse. Fearful of forgetting the gentle expression on its face, the little dreamer jumps quickly to her feet. All that can be seen of her in the deepening dark of twilight are her eyes, shining bright to illuminate her path as she skips back home.

Taylor Marie Prendergast

Through her work, Taylor Marie Prendergast investigates the tension between tender and ferocious aspects of domesticity. In her drawing, Vow (2025), created specifically for the exhibition, Prendergast presents a scene that is both tranquil and charged. In Claudine’s House, Colette writes with a vehement sensitivity to what animates the home, with animals, gardens, siblings, and rituals becoming mirrors for human desire. Prendergast engages with this same emotional terrain. Like Colette, Prendergast renders the animal presence as central. A dog appears still, yet alert, as if aware of something unsaid in the room. The subject's poses are natural, almost gentle, but the starkness of the surrounding environment and the intensity of the dog’s gaze suggest a latent alertness—a readiness to respond, protect, or flee. This ambivalence lies at the heart of Prendergast’s inquiry: how intimacy and discomfort, affection and anxiety, often coexist in domestic life.

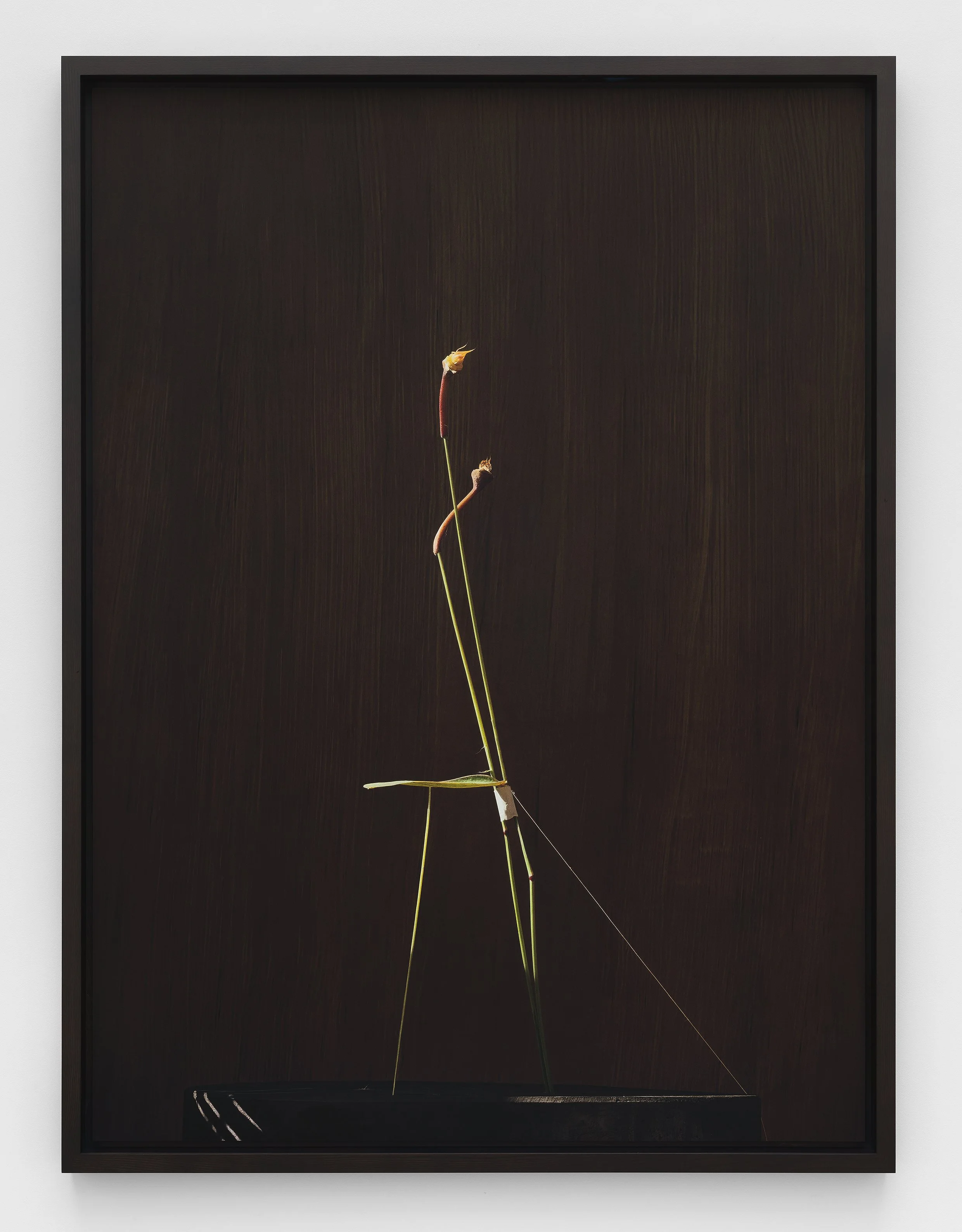

Dominik Tarabanski

In his photographic series, Roses for Mother, populating the entire Eastern wall of the gallery, Dominik Tarabanski explores the tension between impermanence and control, transforming vestiges of everyday life—metal clips, rubber bands, gaffer tape, fruit nets—into scaffolding for botanical characters that are stretched, clipped, suspended, and contorted into complex compositions. What began as a series of personal “postcards” sent to his mother, each one capturing the mood, atmosphere, and flora of the places he traveled, has evolved into a visual language, an archive of care and transformation. These works do more than document botanical arrangements, they become surrogate letters, recording fleeting sensations of place through a language of petals, stems, and the leftovers of living.

Each composition is both tender and tense: blossoms appear mid-monologue, petals droop like bowed heads, stems bend as if under emotional weight. The artist’s final images, often requiring hours of focused work, subtly reveal traces of their own making—a visual archaeology of process. In the background, pollen, dust, soil, discarded clips and ties, rolls of gaffer tape, and scattered petals remain, his compositions openly acknowledging the choreography of their creation. The tonal and textural variations of his backdrops—some soft and diffused, others harsh or theatrical—suggest emotional weather as much as physical setting. Evoking not only geographic specificity but the intangible moods that linger in memory, the environments these flowers inhabit are as crucial as the subjects themselves.

Both Colette and Tarabanski investigate imperfection as a truth-telling force. Colette writes with an unflinching eye, capturing the unsaid and unkempt in the domestic sphere, resisting a tidy portrait of life. Similarly, Tarabanski does not present his floral subjects in a state of idealized bloom but allows them to resist, to decay, to sag, to struggle for balance. The beauty of both Colette and Tarabanski’s images lies not in their flawlessness, but in their candor and vulnerability.

Installation Views

Images courtesy of Ross + Kramer Gallery New York. Photography by Grace Dodds.

A selection of Peter Hoffmeister’s work photographed by Alexander Perrelli.

Images of Anders Hamilton’s work courtesy of the artist.